Biodiversity in South Asia - A Mini Report on the State of Biodiversity Across Southern Asia

Introduction

Southern Asia is a region infamous for its outstanding natural beauty and abundant biodiversity. From the great flowing river Ganges to the Himilayan mountains to the dense jungles of the Western Ghats to the brilliant coral reefs of the Indian Ocean, Southern Asia is a paradise for naturalists, scientists, conservationists and tourists alike. The regions capacity to sustain life and to produce societies and cultures which have found ways to work in harmony with nature has been something to behold, unfortunately, South Asia is fast losing its balance and today the fight is on to rescue and preserve biodiversity across the region. This mini report provides an overview of how our presence in Central Asia is impacting on the natural world and presents three regional case studies; India, Bhutan and the Maldives to illustrate biodiversity in a national context.

The State of Biodiversity in Southern Asia

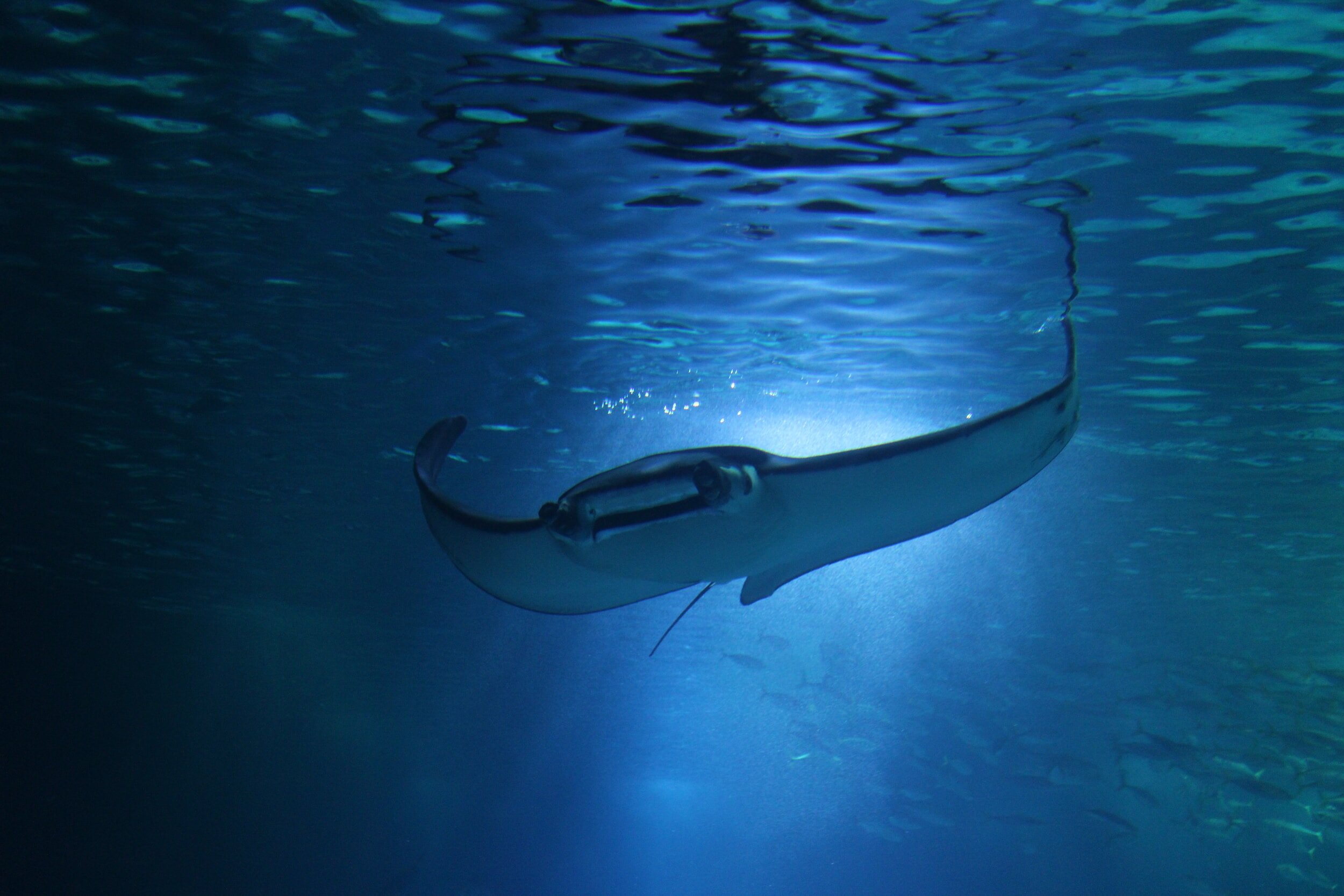

South Asia is one of the world’s greatest biodiversity hotspots, home to 15.5% of all known plant species and 12% of all known animals (Chaudhary, 2023) its ecosystems are brimming with life, housing some of the rarest and most endangered species on the planet. This wealth of natural resources has over time given rise to a deep connection and dependance for human activities such as agriculture, forestry and fishing. Unfortunately, that dependence has led to a system wherein human communities are taking far more than they are giving back and the result has been that they have failed to meet the milestones put in place to protect natural spaces - the global minimum target of protecting at least 17% of land by 2020 and likely the Global Biodiversity Framework’s 2030 target to protect at least 30% of land which is set to be missed by an even greater margin - the outlook is in fact worst for South Asia who are only set to achieve 10% coverage of protected areas (Farhadinia, 2022). In part this unequal relationship and the failure to meet targets that protect just the bare minimum of biodiversity has proved problematic due to rapid population growth and all the urbanisation, infrastructure and consumer demands which go with it. These factors have in turn produced a fall out of pollution, over-exploitation and now climate change (Chaudhary, 2023) which is forcing crucial South Asian biodiversity and possibly entire nation states to the brink of extinction. If we were to build a picture of South Asia in our minds today it would be filled with contrasts from the vast structures of India’s silicone valley in Bangalore to the ancient temples which almost appear to be growing out from the mountains of Bhutan, the old and new exist side by side, yet our images of biodiversity are no less spectacular but are fading as the giant manta rays of the Maldives disappear as our oceans warm and Asiatic lions are forced into conflict with human settlements as they struggle to cope with habitat loss. Finding a way through the complex maze of development and conservation is one that cannot be tackled alone and it is for this reason that the region has come to a general consensus that cooperation and collective efforts are the only way forward if they wish to ensure ecological security and reduce the regions vulnerability to climate change. “The cross-border consequences of climate change and ecological degradation demand collaborative action. National or even sub-regional solutions are not enough” (Saran, 2021) and so, despite the various political, ethnic and religious tensions and the competing commercial and economic interests which often blight the region, a reluctant consensus has been reached that the way forward will necessitate compromise and a willingness to work together for a greater cause. The transboundary nature of South Asia’s ecosystems has great potential to produce some of the first truly effective cooperative actions through a mixture of region wide policies and practices, something which is still yet to be fully explored. There have already been a number of success’ at a bilateral and multilateral level such as an agreement between India and Nepal signed in 2019 to increase joint patrolling in transboundary habitats and capacity building officers engaged in wildlife conservation or in the World Bank funded establishment of the South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network (SAWEN) which is aiming to develop a set of protocols on sharing data relating to illegal wildlife trade, and to develop regional capacity in wildlife forensics (Chaudhary, 2023). As of 2018 the South Asian nations had taken action to protect their wild species and habitats by establishing some 1,625 protected areas covering 361,367 km², or around 8% of the land surface (European Commission, 2019), however, the actions taken thus far have garnered both praise and criticism over the effectiveness of these protected areas in maintaining biodiversity and reducing species population loss. It appears that South Asia as a region is beginning to take valuable steps towards protecting biodiversity, yet, their work as a collective is yet to make a sufficient enough impact so as to reduce the overall decline in regional biodiversity. However, if we are to take a closer look at the individual nations which make up South Asia we can quickly see just how diverse responses have become and that though their may be deep set divisions in many countries biodiversity is one area which bridges those divides and brings together distant communities.

India

India is the largest geographical spaces in South Asia and has been recognised as one of the world’s mega-diverse countries as 7-8% of all recorded species call India home. “Over 91,200 species of animals and 45,500 species of plants have been documented in the ten biogeographic regions of the country… along with species richness, India also possesses high rates of endemism. In terms of endemic vertebrate groups, India’s global ranking is tenth in birds, with 69 species; fifth in reptiles with 156 species; and seventh in amphibians with 110 species. Endemic-rich Indian fauna is manifested most prominently in Amphibia (61.2%) and Reptilia (47%)” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). India holds a significant portion of its biodiversity, particularly its 758 most vulnerable and endangered species, in the wide range of ecosystems and habitats such as forests, grasslands, wetlands, deserts, and coastal and marine ecosystems (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). In fact, you would be hard pressed to find an ecosystem India does not have! India could still be full of surprises as the region’s biodiversity remains critically undocumented and understudied, for example only 190,000 of their various plant and animal species have been named, which shows the true dearth of knowledge on India’s biodiversity and its crucial ecosystems (Sengupta and Dayanandan, 2022). There has never been a better time for a reevaluation of both India’s status as a biodiversity hotspot, particularly as the nation has lost <30% of its natural vegetation and in their capacities to protect the various flora and fauna which are struggling to adapt to a rapidly changing landscape. We must collectively take the time to examine both what threatens biodiversity in India and what actions can be taken to alleviate those issues, thereby conserving India’s unique and vibrant biodiversity. Afterall, the assortment of issues which face modern India range from climate change to an ever expanding population which brings all of the concomitant pressure related to provision a growing populous. The tangled web of complex social, cultural and economic issues which pertain to the use, protection and conservation of biodiversity in India will prove something of a challenge to overcome, however, they can be combatted both individually and collectively through a mixture of traditional and modern innovative solutions. For those solutions to be put into practice, however, India will need the necessary financing and that is where we hit something of a snag as Vinod B. Mathur, India's official delegate to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in Nairobi stated clearly India received around $10 billion a year in funding between 2017-2022 which is still a far cry from the $16.5 billion required leaving the nation with a significant shortfall in biodiversity finance (Lopes, 2022). This finance gap will in turn leave many ecosystems and species vulnerable to the other pressures placed on India’s biodiversity such as;

Habitat fragmentation, degradation and loss,

Over-exploitation of resources,

Shrinking genetic diversity,

Invasive alien species,

Declining forest resource base,

Climate change and desertification,

Impact of development projects,

Impact of pollution (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023),

Increasing population densities (and the concomitant exacerbation of anthropogenic pressures such as deforestation and overharvesting) (Sengupta and Dayanandan, 2022),

Economic development (agricultural expansion and urbanisation, coupled with vegetation greening - indicative of increased year-round irrigation in agricultural areas),

Unsustainable land-use practices,

Hydropower dams and road networks,

Expansion of oil palm plantations,

Climate change (temperature increases, rainfall anomalies and major floods) (Srivathsa et al., 2023),

Overexploitation of marine resources,

Waste dumping (in waterways and in the ocean),

Deforestation of mangrove forests,

Sea level rise (Raghunathan et al., 2019).

Though India is facing many similar issues to nations around the world in terms of the factors which are contributing to a decline in biodiversity and in attempting to implement effective long-term protective actions and policies, they do also face some more unique challenges due to the sheer geographical expanse of the region, the complex, often slow bureaucratic systems used for policy implementation and the scale of difficulty involved in balancing the needs of one of the fastest developing nations on the planet with the biodiversity and ecosystems upon which this development continues to rely. Though India has already begun to implement a number of protective policies to be carried forward by both the public and the private sector there is still a long road ahead. Thus far they have “established a network of 679 Protected Areas (PAs), extending over 1,62,365.49 km2 (4.9% of the total geographic area) and comprising 102 National Parks, 517 Wildlife Sanctuaries, four Community Reserves and 56 Conservation Reserves” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). These protected areas cover some of India’s most vulnerable species and have seen success if increasing the numbers of lions, elephants and the once endangered now vulnerable rhino’s. The multifaceted approach on the part of the Indian government has focused in large part on the nations forests as numerous programmes have been instituted as part of their wider reforestation in an effort to meet the National Forest Policy aims to maintain a minimum of 33% of the country’s geographical area under forest and tree cover. However, the government has also worked on “conservation and sustainable development, eco-development of degraded forests, development of community conservation reserves outside PAs, economic valuation of ecosystem services and climate change, and finally inculcating awareness and imparting training to a range of stakeholders, including school students, ex-servicemen, farmers, Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs), extension workers, community groups, etc.” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). It appears that India’s cultural consciousness relating to the value of biodiversity and the need for conservation alongside the implementation of newer, more holistic policymaking has paid dividends as the nation managed to achieve the global Aichi biodiversity target of protecting 17% of terrestrial areas whilst also managing to introduce the India Biodiversity Awards (IBA) which incentivise individuals and institutions who worked tirelessly towards conservation and sustainability (Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change and UNDP, 2022). It is not only the Indian government who are making strides towards a more biodiverse world, The National Mission on Biodiversity and Human Well-Being has debuted after being set up by Indian conservation biologists and ecologists to help fill the gaps in the knowledge of India’s biodiversity. The core of the mission will be to “document and map India’s biodiversity, including its rich biocultural diversity, to enable conservation and sustainable use of biological resources” this will also be linked to six smaller programs seeking to restore biodiversity in a range of habitats–grasslands, forests, wetlands etc. (Ghosh and Kasambe, 2020). The increased protection of India’s wild spaces and the inclusion of community based conservation efforts its making a big difference to the survival of some of India’s most endangered and vulnerable species and ecosystems. If India can find a way forward that is inclusive of both its economic and biodiversity needs then they will have a real chance of restoring some of South Asia greatest natural spaces.

Bhutan

This mountainous kingdom in Southern Asia has made a name for itself as one of the greenest, most biodiverse, only carbon negative nations on the planet (Nguyen, 2022) and though this small, landlocked country keeps a relatively low profile on the international circuits they do represent one of the most significant examples of how a nation can value biodiversity in the 21st century. Bhutan is known to have selective policies when it comes to modernisation and has in large part chosen to swim against the tide of economic and industrial development, instead, choosing to retain traditional cultural practices and find policies which strike a balance between providing the Bhutanese population with opportunity and growth whilst still protecting crucial ecosystems and rare species. Even given Bhutan’s relatively small size it in fact a biodiversity hotspot and is counted among the 234 globally outstanding eco-regions of the world by the World Wildlife Fund. “Bhutan has six major agro-ecological zones corresponding with certain altitudinal ranges and climatic conditions (e.g. alpine, cool temperate, warm temperate, dry subtropical, humid subtropical, wet subtropical)”. For the most part forest cover has remained relatively well-preserved at 70.46% of total land area and their inland water resources such as rivers, rivulets and streams have avoided the pollution levels of their Indian neighbours. The untouched nature of Bhutan’s ecosystems has translated itself into “strong species diversity and density, with about 5,603 flowering plant species… close to 200 species of mammals (which is extraordinary for a country which is one of the smallest nations in the Asian region), 800 to 900 species of butterfly and 50 freshwater fish species (with overall fish fauna not yet properly assessed in the country)... 23 species of reptiles and amphibians exist in the country… the country is (also) enormously rich in bird and crop diversity, with 678 bird species recorded, 78% of which are resident and breeding, 7% migratory and 8% winter visitors” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). This mass of nature are safeguarded through a mixture of protected areas and biological corridors which provide sanctuary to some of the regions most vulnerable creatures. As of Bhutan’s fourth national report one critically endangered mammal species, 11 endangered species and 15 vulnerable species call the country home (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023) and with more than 51% of the country formally protected - the largest of any Asian country, Bhutan is set to remain a safe haven for wildlife in Southern Asia (WWF, 2023). This commitment to conservation is shown in the number of endangered royal Bengal tigers, elusive snow leopards, elegant black cranes and elephants—all of whom roam free. Bhutan’s approach to biodiversity may provide something of a breath of fresh air, however, even they are not able to elude the pressures which manage to cross their borders or which are induced by a population looking to find its place in the world such as;

Land conversion,

Overexploitation,

Dependence on wood for fuel,

Pollution by domestic sewage,

Climate change (Melting glaciers & Flooding (Banerjee and Bandopadhyay, 2016) ,

Forest fires,

Needs for forest products,

Infrastructure development,

Population growth and living space requirements,

Rapid urbanization,

Agricultural expansion,

Grazing pressures,

Unsustainable cropping practices,

Agricultural land conversion,

Cultivation of exotic agricultural crops,

Land degradation in the form of erosion (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023),

There is no denying that Bhutan faces similar difficulties to many nations in protecting biodiversity, however, they are miles ahead and have far less ground to cover than many of their neighbours. The two major stressors for Bhutan are likely to be those associated with the use of natural resources to support the 69.1% of their population which directly rely on agriculture and forest resources (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023) and in climate change which does not respect borders and will affect them most in the form of flooding caused by melting glaciers and fluctuations in weather patters which will have a domino effect on both biodiversity and agriculture (Banerjee and Bandopadhyay, 2016). Afterall, Bhutan has changed more in the past 50 years than it has in the past 500 years combined. Demographics has changed with 60% of the nations population now under 34, many of which are looking to new industries and cities to fulfil their needs, leaving behind rural areas with a vacuum of “stewards of the land” (WWF, 2023). Nevertheless, Bhutan has deployed boots on the ground to help bolster biodiversity and are strong advocates for sustainability and climate change on the international stage. In 2011 Bhutan signed the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing to allow for further international collaboration through the setting up of The National Biodiversity Centre designed to provide access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization at the 44th Commission meeting of the National Environment Commission (NBC, 2023). In almost consecutive years Bhutan revised its National Action Programme in 2013 and in 2014 they ensured full alignment with the global Aichi Biodiversity Targets under the UNCBD resulting in the review of 40 policies, legal instruments and strategies through a biodiversity lens, an attempted first integrated approach to a Biodiversity and Climate expenditure review which resulted in a framework that can track biodiversity and climate expenditures on a periodic basis, an informed policy dialogue on innovative finance and a demonstration of how ecotourism can be a financially feasible solution (BIOFIN, 2023). It is not only finance that has been on Bhutan’s mind, the government and their royal family have also taken a community based approach through tree planting. In 2015 Bhutan broke the world record for the most tree’s planted in one hour in the country’s capital Thimphu as a team of one hundred volunteers got their hands in the ground to plant a total of 49,672 trees. The following year to mark the birth of a new prince thousands of people together planted 108,000 tree saplings to celebrate the joyous occasion, these trees are still being nurtured proving that tree planting does not have to be an exercise in corporate greenwashing (The Australian National University, 2016). One of the most recent milestones in Bhutan’s conservation timeline has been the creation of Bhutan for Life in 2018 which procured a $43 million fund—the first of its kind in Asia—to permanently protect Bhutan’s network of protected areas. This funding was then combined with a further $75 million from the Bhutan government over a 14-year period which commenced in 2018. This new programme is all about achieving balance in Bhutan by allowing sustainable economic development, such as eco-tourism and organic farming in protected areas (WWF, 2023). The list of Bhutan’s biodiversity achievements and milestones they plan to reach would make up a report all to themselves and though Bhutan will no doubt have to find solutions to the various challenges the modern world brings with it there is no doubt that this strong willed nation will continue to be a shining light for conservationists and environmentalists across Southern Asia whilst also proving that it is possible to develop but not at the cost of the environment.

The Maldives

The Maldives might just be one of the most beautiful, awe-inspiring and diverse island nations on the planet, yet, it is rapidly becoming a symbol of climate change in South Asia as rising sea levels threaten its very existence and rising temperatures damage the ocean ecosystems upon which its people rely. The 1,192 tiny islands which make up the Maldives are for the most part low-lying coral islands which have formed 26 natural atolls. Their being surrounded by a great expanse of ocean means however that the lions share of their biodiversity comes in the form of coral reefs and various other forms of marine life. “The coral reef systems of the Maldives are the seventh largest in the world and cover an area approximately 8,900 km2 in size, which is approximately the fifth most diverse ecosystem of the world’s reef areas… The Maldives has a total of 1,100 species of demersal and epipelagic fish, including sharks, 5 types of marine turtles, 21 species of whales and dolphins, 180 species of corals and 400 species of mollusks. There are 120 species of copepods, 15 species of amphipods, over 145 species of crabs and 48 species of shrimps. There are also 13 species of mangroves and 583 species of vascular plants. Additionally, two species of endemic fruit bats have been found. The bird species number 170 of which most are sea birds (103 of these birds are protected)” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). Naturally, the terrestrial diversity of the Maldives is limited due to is geography - the islands are small and nearly three-quarters of available land is less than one metre above high tide, there is also an absence of large bodies of freshwater to support a wider terrestrial system. Be that as it may the Maldives make the most of what they have and rely heavily on “natural resources for its national income, food and other basic needs. A study done on the economic values of biodiversity indicates that 98% of national exports, 89% of the GDP, 62% of foreign exchange and 71% of national employment are derived from biodiversity” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). For the most part the biodiversity this is in reference to is the abundance of marine life across the Indian Ocean which was recognised by the nations president in the Forward to an IUCN report where he stated “the Maldives’ unique environment is the bedrock of our economy. Fisheries and tourism, our two largest industries, are heavily dependent on a healthy and diverse marine ecosystem. Together, these two industries provide three quarters of our jobs, 90% of our GDP and two thirds of our foreign exchange earnings. Moreover, healthy coral reefs help protect our islands from natural disasters and guard against the adverse affects of climate change” (Ministry of Housing, Transport and Environment, Government of Maldives, 2009). Successive Maldives government’s have been particularly vocal on climate change and the impacts it has on marine ecosystems, particularly as coral bleaching and warming ocean temperatures can have such a devastating impact for the nations economy. Evidence once again of how conservation and the protection of biodiversity actually benefits an economy more than exploiting these natural resources for short term gain. Unfortunately, a mixture of both external and internal factors are putting pressure on the Maldives biodiversity, some of which are;

Anthropogenic activity (such as tourism and over-exploitation without consideration given to biodiversity),

Pollution (from uncontrolled waste disposal, untreated sewage and land reclamation and channel building are major threats to the biodiversity),

Unsustainable agricultural practices (such as overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides),

Removal of vegetation for infrastructure and human settlement, and developmental practices (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023),

Lack of environmental integration across sectors; and more importantly biodiversity conservation is accorded only a minor priority in economic policy formulation, financial planning and programme implementation,

Public investment in conservation, especially, remains extremely low. Over the last 5 years environmental spending has consistently accounted for less than 1% of all public sector budget allocations. Patterns of donor assistance present a similar picture: environmental spending constitutes just 3% of ongoing programme and project support to the Maldives (Ministry of Housing, Transport and Environment, Government of Maldives, 2009),

Destruction of habitats (including reefs, lagoons, beaches and mangroves due to land reclamation, habour building, channel construction, seawall construction and many related infrastructure development activities),

Beach erosion (over 60% of the inhabited islands report severe beach erosion threatening not only biodiversity but also human settlements) (Ministry of Environment and Energy, Government of Maldives 2015),

It is a cruel set of circumstances that the Maldives should be so vulnerable to external threats which they can do little to change beyond making consistent appeals to the international community to stop the runaway train that is climate change. Nevertheless, they have not resided themselves to a fate that is as yet undecided and are continuing to forge ahead in the areas where they can make changes. The Maldives face a similar challenge to many Small Island Developing States (SIDs) as protection of marine areas, which today cover 428, 569 hectares including ecosystems ranging from dive sites to mangroves (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023), make up the bulk of their biodiversity and can prove equally challenging in the protection implementation stages and in their continued conservation as similar programmes based on land. With so many species passing through the nations waters or stopping off on land for breeding, laying eggs or feeding the scale of protection required and the helpless feeling which can be induced after creatures chose to leave the nations marine borders and become vulnerable to issues such as overfishing can prove overwhelming at times. The Maldives are mindful of how crucial their small island ecosystems are, particularly to some of the larger and more famous marine fauna such as turtles, who are now protected from being exploited and exported by a ten-year moratorium and whale sharks whose aggregation area was declared a marine protected area in 2009 with a ban on shark fishing swiftly following in 2010(Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023). Often such exploititative activities would have fed into the tourist industry but the government of the Maldives is also working to change the way the tourism effects its biodiversity by restricting activities in the house reefs of the 112 resort islands to snorkeling, ensuring only low impact tourism which stills brings a financial boost to the local community. It is also important to recognise the contribution being made to improve community awareness either through the conservation fund which sprung up as part of the declaration of Baa atoll as a UNESCO Biosphere reserved which provides finance to promote sustainable livelihoods, conservation, education and research (Ministry of Housing, Transport and Environment, Government of Maldive, 2009). More recently “the EU funded the SWITCH-Asia Prevention of Marine Litter in the Lakshadweep Sea (PROMISE), a four-year project 2020-2024) aiming to collect up to 1000 tonnes of little from the Lakshadweep shorelines in the Maldives, Sri Lanka and India”. As part of the projects activities which are aimed at raising awareness on marine little prevention among local communities beach clean-up events have been taking place with increasing frequency (SwitchAsia, 2022). NGO’s from across the globe as well as grassroots NGO’s have also been quick to heed the conservation call, from the Blue Marine Foundation managing in just three months to convince more than a quarter of all resorts in the Maldives to stop removing seagrass to make clear lagoons around their resort islands (Blue Marine Foundation, 2023) to The Maldives Resilient Reefs Project which works on the ground with community led projects inspiring local people to become reef guardians and to continue the drive for a consistent fishing ban on sharks (The Maldives Resilient Reef Project, 2023). Everywhere you look today the Maldives are teaming with activists and passionate conservations at every level of society all hoping to make a difference and continue the drive towards a more sustainable future relationship for the Maldives people and the marine ecosystems. Though there will no doubt be challenges ahead, many of which having been caused by forces beyond their control, biodiversity has a chance to truly thrive if the people of the Maldives work collectively and mindfully for marine life.

References

The Australian National University. “Biodiversity is a place; Bhutan.” Biodiversity Conservation, 14 October 2016, https://biodiversityconservationblog.com/2016/10/14/biodiversity-is-a-place-bhutan/.

Banerjee, Aparna, and Rajib Bandopadhyay. “Biodiversity hotspot of Bhutan and its sustainability.” Current Science, vol. 110, no. 4, 2016, pp. 521-527, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24907908.

BIOFIN. “Bhutan.” BIOFIN, 2023, https://www.biofin.org/bhutan.

Blue Marine Foundation. “Maldives - Blue Marine FoundationBlue Marine Foundation.” Blue Marine Foundation, 2023, https://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/projects/maldives/.

Chaudhary, Sunita. “Opinion: Regional cooperation in South Asia crucial for meeting biodiversity targets.” The Third Pole, 10 February 2023, https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/regional-cooperation/opinion-regional-cooperation-in-south-asia-key-to-meeting-biodiversity-targets/.

Convention on Biological Diversity. “India - Main Details.” Main Details, 2023, https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=in.

Convention on Biological Diversity. “Main Details.” Main Details, 2023, https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=bt.

Convention on Biological Diversity. “Main Details.” Main Details, 2023, https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=mv.

European Commission, Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development. “Larger than tigers – Inputs for a strategic approach to biodiversity conservation in Asia : regional reports.” Publications Office, 2019, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2841/046399.

Farhadinia, Mohammed. “Study finds most Asian countries are far behind biodiversity targets for protected areas.” University of Oxford, 29 November 2022, https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2022-11-29-study-finds-most-asian-countries-are-far-behind-biodiversity-targets-protected-areas.

Ghosh, Sahana, and Raju Kasambe. “Bringing biodiversity and conservation to the forefront in India.” Mongabay-India, 10 December 2020, https://india.mongabay.com/2020/12/bringing-biodiversity-and-conservation-to-the-forefront-in-india/.

Lopes, Flavia. “'India Needed $16.5 Billion For Biodiversity Conservation between 2017-2022. All we had was $10 Billion.'” IndiaSpend, 2 July 2022, https://www.indiaspend.com/indiaspend-interviews/india-needed-165-billion-for-biodiversity-conservation-between-2017-2022-all-we-had-was-10-billion-824502.

The Maldives Resilient Reef Project. “Why it is crucial the Maldives remains a shark sanctuary?” Maldives Resilient Reefs: SaveOurSharks, 2023, http://www.maldivesresilientreefs.com/saveoursharks/.

Ministry of Environment and Energy. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025. Ministry of Environment and Energy, Maldives, 2015, http://www.environment.gov.mv/biodiversity/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/NBSAP-Maldives-2016-2025.pdf.

Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change and UNDP. INDIA, NATURALLY! Celebrating Champions of Biodiversity. 4 ed., UNDP, 2022, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-06/India%20Naturally%20Fourth%20Edition.pdf.

Ministry of Housing, Transport and Environment, Government of Maldives. Valuing Biodiversity, The economic case for biodiversity conservation in the Maldives. Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, IUCN, International Union for the Conservation of Nature for the AEC Project, Ministry of Housing, Transport and Environment, Government of Maldives., 2009, https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2009-115.pdf.

NBC. “About NBC.” National Biodiversity Centre: Home, 2023, https://nbc.gov.bt/.

Nguyen, Lei. “Bhutan: The First Carbon Negative Country In The World.” Earth.Org, 18 August 2022, https://earth.org/bhutan-carbon-negative-country/.

Raghunathan, C., et al. “Coastal and Marine Biodiversity of India: Challenges for Conservation.” Coastal Management, Global Challenges and Innovations, vol. 11, 2019, pp. 201-250, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-810473-6.00012-1.

Saran, Shyam. “South Asia needs a united voice at UN climate, biodiversity meetings.” World Bank Blogs, 22 April 2021, https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/south-asia-needs-united-voice-un-climate-biodiversity-meetings.

Sengupta, Asmita, and Selvadurai Dayanandan. “Biodiversity of India: Evolution, biogeography, and conservation.” Special Issue: India’s Biodiversity: Evolution, Biogeography and Conservation, vol. 54, no. 6, 2022, pp. 1306-1309. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.13168.

Srivathsa, A., et al. “Prioritizing India’s landscapes for biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being.” Nature Sustainability, vol. 6, 2023, pp. 568–577, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01063-2.

SwitchAsia. “The Maldives and the EU close partners in the fight against climate change and the protection of biodiversity and our oceans ›.” SWITCH-Asia, 28 November 2022, https://www.switch-asia.eu/news/the-maldives-and-the-european-union-close-partners-in-the-fight-against-climate-change-and-the-protection-of-biodiversity-and/.

WWF. “Bhutan: Committed to Conservation | Projects | WWF.” World Wildlife Fund, 2023, https://www.worldwildlife.org/projects/bhutan-committed-to-conservation.